Can the Cognitariat Speak? - taken from eflux, 2010

Isabelle Bruno is a French political scientist who has written on the range of mechanisms used by the European Union to regulate and redefine the public sector.1 Christopher Newfield is an American cultural studies scholar who has written about innovation and the fate of public higher education, including the “budget wars” over the arts and humanities.2They met as co-panelists at a conference in Toulouse in the fall of 2008. Organized by the association Sauvons la Recherche, the conference explored opposition and alternatives to the neoliberalization of higher education as envisioned by the Sarkozy government in France, influenced by British and American examples.

What can the world’s knowledge workers—the cognitariat—do about their current social and institutional predicaments? American management theorists like Peter Drucker have long argued that the knowledge workers would inherit the earth—or at least the economy.3European critics of capitalism like Antonio Negri and André Gorz also noted the tendency of capitalism toward monopoly control of everything, knowledge included.4But they agreed with Drucker and Daniel H. Pink that the increasingly immaterial or cognitive status of worker know-how allowed it to belong to—and therefore be controlled by—its individual possessors.5 The members of this cognitariat, for Drucker, Negri, and Gorz alike, are not therefore a new proletariat, but a new knowledge class with new strengths to bring to bear in ongoing conflicts with capitalism, which has itself been changed by the new ubiquity of knowledge.6

What follows is a dialogue based on five hours of discussion between Bruno and Newfield one Saturday afternoon in Lille, in January 2010. The original discussion was conducted in French.

***

Christopher Newfield: In my adult lifetime I’ve lived through a revolution—the business revolution, in which the codes of business judgment have presented themselves as universal knowledge. Lyotard was misread in the 1980s as defining the postmodern condition as the “end of master narratives.” The opposite has happened: business became the global master narrative, the fountainhead of the transcultural “Lexus” refuting the situated knowledge of the “olive tree,” to revert to the title of the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman’s 1990s business bestseller. Businessmen populate the boards of trustees of American universities and subject nonprofit activities like education to financialization and cost-cutting techniques, and give philanthropic dollars to fields most likely to offer economic returns on investment. Little thought is given to the social and public value education creates that can’t be captured through accounting. Even neoclassical economics has a word for public value that cannot be captured by a particular firm—“spillovers.” But business does not have such a term, and in education, science, journalism, and art, public value is hard to talk about.

Isabelle, you analyze subtler modes of the “businessing” of everything. In your Toulouse talk, and in your book on the Lisbon process, you showed how the European Commission has developed a range of arcane techniques and strategies designed to make public systems serve the economy rather than society. Michel Foucault has described this as neoliberal governmentality (what had been referred to in Europe as “ordoliberalism”). Neoliberal governmentality made the European Union serve business first and the population second, and serve the population only in ways that were good for business. I was also struck by your manner. You really “belted it out,” as we sometimes say of strong passages by our favorite singers. Later that day you were on French public radio, on France Inter’s science show, “La tête au carré,” with several “big heads,” including the recent Nobelist in physics, Albert Fert, and you more than held your own, especially against Fert’s “grand old man” complacency about the government’s efforts to increase the share of research funding coming from industry. I thought of you as a fighter, perhaps even “competitive.” Then when we met again at the biannual FOREDUC conference in Paris, organized by Carole Sigman and Annie Vinokur, you denounced competitiveness as the corrosive logic of the European Commission’s administrative war on the public sector. What’s your relation to competition?

Isabelle Bruno: On the personal level, competition just never motivated me. As I was growing up in the south of France I did very well in school—I never felt unsuccessful in relation to the French practice of public rankings of students. And yet there was nothing motivating about it. I gave up tennis because of that. It was fun to play but then at the end there were these competitions and they didn’t inspire me, keeping score and that framework for playing. Competition didn’t express what I liked about playing. I push myself quite a bit: I am very demanding towards myself. But competition never actually pushed me. One can demand a lot of oneself without needing to compare oneself to others to be sure to be better than them.

Neoliberalism is a philosophy—an anthropology—of human relations that makes competition the organizing principle of society. That would be fine for some sectors, obviously sports, maybe even the economy that surrounds large corporations. But what disturbs me now is the application of this anthropology of competition to all human activities. It’s that totalitarian, that totalizing aspect that I critique. It denies autonomy to varying sectors of activity—education, the arts—by refusing to acknowledge that these sectors have their own principles of organization. Competition isn’t the problem in itself. The problem is its claim to be the sole principle of society.

CN: A world divided into winners and losers seemed to me like something I had grown out of. I was an obsessive baseball fan between the ages of six and ten, and on some mornings would burst into tears when I discovered that the Los Angeles Dodgers had lost an important game. But then the world got bigger and I stopped caring. Now I think more about the psychological effects of contexts in which most people are losers. Competition is the cornerstone theory of neoclassical economics, and is a sacred principle in the U.S. Competition is equated with freedom—freedom to compete, no barriers to entry—and with quality, since competition among all parties is supposed to identify the winner and move resources towards that person or firm. In other words, competition showed in the 1980s that Dell Computer was a better third-party provider of cheap personal computers than Leading Edge, and the economy and society benefitted by showering resources on the better firm Dell.

In your work, Isabelle, you show the European Union taking the same neoclassical position on competition. Europe is supposedly too well protected, and its people are too protected to hustle like the Americans, the South Koreans, and the Chinese. So their economies will be richer and their societies more dynamic if they replace protection with open competition. That, in turn, if one follows Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of “creative destruction,” which all economic-policy people seem to, leads to higher rates of innovation, more wealth, perhaps even better art.

Leaving aside the theoretical problems with this model, which have been pointed out repeatedly, I have the same basic feeling about competition as you do—it’s just not inspiring. It’s also destructive, and thus it shouldn’t structure everything in society. There is a major, undeclared culture war between those who think competition makes people smarter and stronger and fixes everything, and those who see it as often harmful. Solidarity is a real counterweight in France, but not in the English-speaking countries.

In my case, after age ten or so sports were largely replaced by novel-reading, where the distribution of joy and suffering involved collective relations and not just competition. The art world, the world in literature anyway, didn’t seem organized around competition . . .

IB: What? The art world isn’t competitive?

CN: No, it is, of course. It’s full of competitive maniacs. But it’s also collaborative. Creativity, I’ve always thought, works through collaboration more than through individual inspiration. The literature on creativity is full of stories of borrowing, stealing, swapping—with some competing, of course. But the spirit of competition cannot overwhelm everything else. The breakthrough moments of sudden insight rest on long periods of preparation that always involve enormous amounts of collective work. If creativity depends on competition, it is because competition leads to some combination of adoption and exchange. Creativity depends on the suspension of defeat. People have to feel undefeated in order to try something new. You can’t try something new if you are focused on defending yourself against others. In this way art is not like a market, which is full of competition and also imitation.

IB: What certainly is true is that elements in any domain that don’t fit with markets are targeted for transformation by the privatizing impulses of the EU’s “New Public Management.” The EU’s relation to knowledge is motivated by a sense that it could lose its competitive edge in the global economy, and its solution is to be more competitive. So the EU’s vision of managing anything is to rate its competitiveness. They rate competitiveness by ranking every institution and function in relation to others. If you are ranked higher, you are by definition more competitive. In this model, value increases proportionately to competitiveness, and competitiveness can be measured objectively by ranking a university or gallery or anything else in relation to others. Germany wanted to improve the position of its universities in the Shanghai world rankings, and its education ministry not only equates rank with quality but also invites foreign students to identify the content of the right program for them by looking at rankings.7

CN: I like two other points you make in your paper. First, you say there’s no evidence that the implementation of “competitiveness” by the European Community has actually done what it is assumed to do—improve educational quality, or EU productivity, or economic growth rates, or something else. And second, you say that the absence of real outcomes doesn’t matter. The goal isn’t to have economic or social benefits, but competitiveness. You describe competitiveness as a kind of existential state, a form of life. You describe the “neoliberal belief” as this: “every institution has as its ultimate end to become competitive, and can achieve this only by being exposed to competition.”

IB: Europe as a “société de connaissance” is really Europe as a “société de concurrence”—research, teaching, innovation are all yoked together in the general pursuit of competitiveness.

CN: I often hope that the university can serve as a platform for enlightened opposition to various regressive trends. But I don’t see that academia has or will resist competitiveness. For one thing, the whole atmosphere of knowledge crisis preserves the university’s social importance. The premium on profitable knowledge links the university with CEOs and wealthy donors rather than with teachers’ unions and government bureaucrats—a big step up Bourdieu’s distinction ladder. And academia is hypercompetitive—reflexively, thoughtlessly competitive. It’s run by people who generally won standardized test contests, and who have spent much of their lives competing for prizes and grant money. They pursue the most publications, the most patents, the most students. None of this has much to do with teaching and learning, with creating new knowledge in poetry or new storage devices for photovoltaic arrays. It is a mechanism for allocating resources, that’s all.

IB: The issue isn’t whether or not you get rid of competition—you can’t. The issue is whether it becomes the overriding organizational principle, or whether it has to coexist with other practices and principles. New Public Management (NPM) tries to drive out other practices.

CN: Exactly. The problem comes when metrics is confused with universal knowledge. Like the Shanghai world university rankings that turned Germany’s research university system—in the country that invented the research university—into a ranked-order competition for more funds on the margins. Or like the bibliometrics mania sweeping the UK, which means that researchers are now competing for the most citations of their publications. How do you actually improve your knowledge creation by doing this? Nobody knows, but that’s beside the point. The point is to replace peer review with citation measurement. What do you think this does to autonomy?

IB: Its goal is to reduce autonomy. These forms of measurement let outsiders in official positions evaluate and come to conclusions about research and teaching performance without understanding the content of what is being taught or researched. That’s when NPM metrics become governmentality.

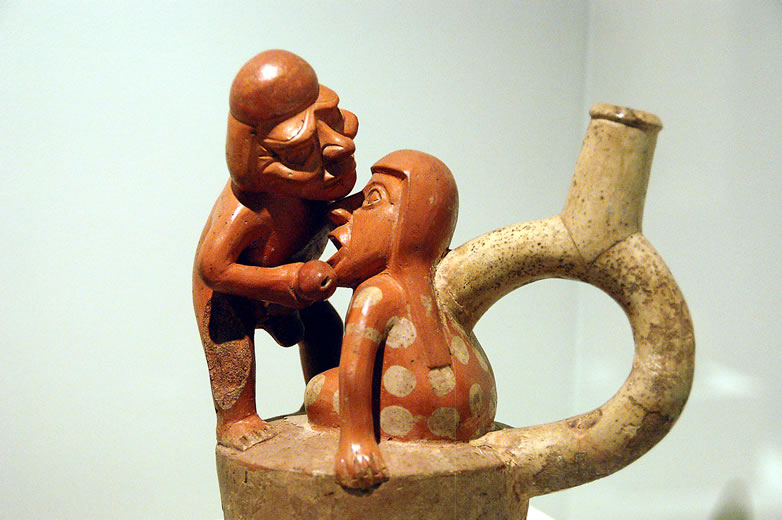

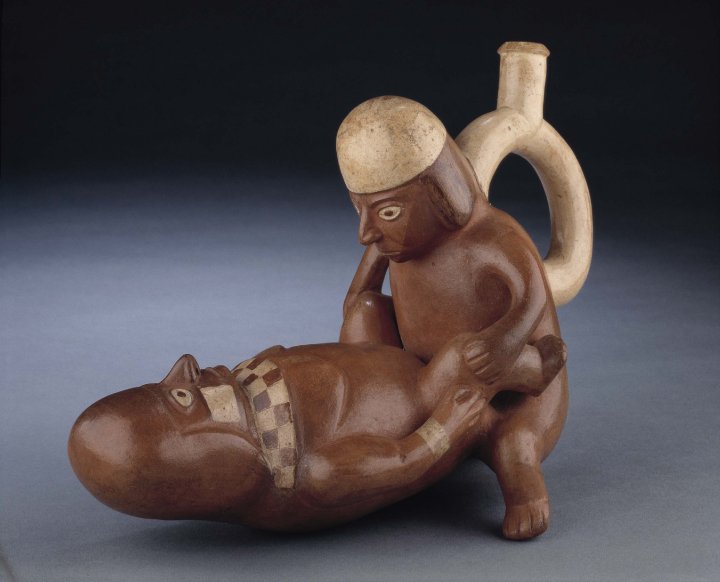

Poster for student demonstrations in Paris, May 27, 2008.

Poster for student demonstrations in Paris, May 27, 2008.

CN: This is where I really become concerned. Academics are bureaucratized intellectuals: they work in hierarchies, have set positions in the structure, positions defined through required procedures, and elaborate, rule-bound protocols through which they relate to their colleagues. The individuals in this kind of system are easily manipulated by rules—do so much publishing in order to be promoted or, under the Research Assessment Exercise in the UK, to not lose money for your department. If each is also in a competitive rivalry with everyone else, there’s little basis for opposition to the ground rules—which in any living system need constant revision. More importantly, there’s less incentive to innovate, to deviate. In a competitive system, the easiest way to lose is to digress from the core assumptions—what Thomas Kuhn called the “paradigm” and what Chris Argyris called the “theories in use” that tell the system what ideas have value.8 Competitive systems are just as likely to be closed as to be open—perhaps more likely to be closed. One major issue that is provoking increasingly widespread critique: it is almost impossible to get a scientific grant with a proposal that doesn’t spell out in advance the discovery to which the research will lead.9

IB: On the other hand, there has been real resistance to ranking in the French higher education system. All sorts of faculty and researchers don’t like it. They see ranking as leading to the loss of professional autonomy, which it is, a form of control administered by non-experts, by managers, by people who work in ministries and who impose these rules. These are norms for teaching and research that are not chosen. They install quantitative measures that override the standards of teaching and research created by the profession.

CN: I was in France in 2009 for the strikes that took place all over the country. Was lost autonomy part of the issue?

IB: It was the core issue. Sarkozy gave a major speech at the end of January 2009 in which he said that French knowledge producers were not globally competitive, that they were less efficient than their peers in England and Germany.10 He mentioned the Shanghai rankings and France’s near-absence from them. His solution was to eliminate France’s national research organization and replace it with a granting agency, so that thousands of independent researchers would need to report to new units and compete for funds. There were many other changes designed to weaken the professional status of French academics. Sarkozy and his higher education minister, Valérie Pécresse, said that the problem was French research inefficiency, and that the solution was less autonomy for researchers. The means for achieving this end would be tighter output controls. Both the problem and the solution rested on the kind of quantitative data mining at the core of NPM and the EU’s vision of the knowledge society.

CN: The national maps of strike activity were impressive: they occurred at some point in the majority of universities in every region of the country. I was in Lyon directing a study center for my University of California students, and those who went to Sciences Po—Lyon had no classes for seven weeks. The strike there was in fact led by that unit’s conservative president, a Sarkozy supporter who was absolutely outraged at Sarkozy’s attack on the quality of French knowledge creation. Still, I’m not sure how deep the opposition is to the managerial cure, to the external monitoring of quantitative output measures, like Frederick Taylor’s “scientific management” developed a hundred years ago.

IB: The opposition has been met by the quiet suffocation of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (National Center for Scientific Research, or CNRS) on the part of the ministry in Paris. They have the power to authorize positions, and as people retire or leave for other jobs, they aren’t being replaced. There’s the danger of a slow decline.

CN: You don’t think the strikes gained something?

IB: We did a lot here in Lille. We left the university and went out into commercial streets to talk to people, to generate interest in the problems of higher education among the citizenry and in the media. It was inventive. We had “les rondes des obstinés.”

CN: Yes, they were great. Some journalists looked at these circular parades of academics that went all day and all night, day after day, and asked “pourquoi vous tournez en ronde”—why do you go in a circle? No matter what happens I will always remember the obstinate perpetual circles.

IB: Yes. And yet the mobilization didn’t have an effect on government policy.

CN: You think the strikes lost?

IB: Completely. We lost on all fronts. The unions don’t want us to say this. They point out that it’s not very motivating to say this. But I think it is more productive to admit we lost a battle in order to carry on the war.

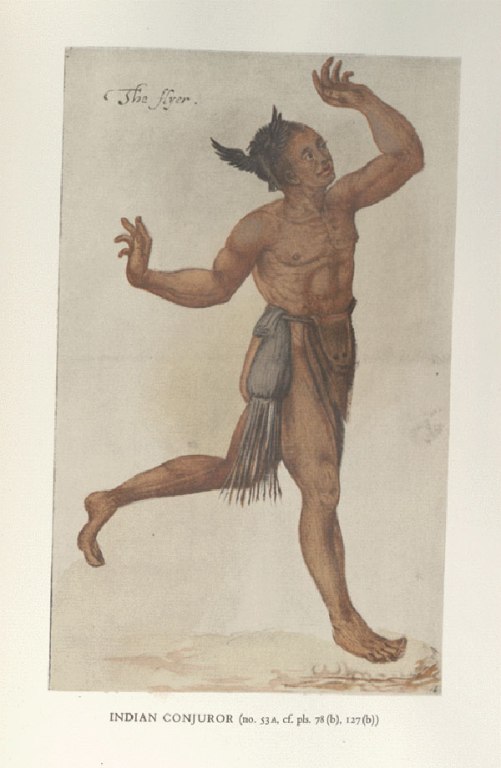

CN: I keep seeing the sheer capacity to persist. When I see the photos of the rondes, I think of the Native Canadian sculptor Bill Reid’s great piece The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, a boat in which all the creatures are competing for control. There is the myth-image of the Raven, who steers, and “although the boat appears to be heading in a purposeful direction, it can arrive anywhere the Raven’s whim dictates.”11 The Obstinés in Reid’s story are represented by the Ancient Reluctant Conscript. Reid explains:

A culture will be remembered for its warriors, artists, heroes and heroines of all callings, but in order to survive it needs survivors. And here is our professional survivor, the Ancient Reluctant Conscript, present if seldom noticed in all the turbulent histories of men on earth. . . . It is also he who finally says, “Enough!” And after the rulers have disappeared into the morass of their own excesses, it is he who builds on the rubble and once more gets the whole thing going.12

Some parts of academia are convinced that they work hand-in-glove with society’s rulers—especially in fields like law and biomedical research. But knowledge creators and teachers are generally more like Reid’s Reluctant Conscripts, following orders while trying to be autonomous, and trying to teach autonomy. Their autonomy always matters, but every once in a while they can build something.

IB: We have a common situation all over Europe. The same counter-reforms are working in every country—this is how I analyze the effects of the Bologna and Lisbon processes coming together to tie knowledge to increased production. There are big national differences in the university systems, but the counter-reforms are the same, and they are provoking similar kinds of resistance.

CN: I think that’s hopeful. I run a blog about the University of California crisis, and I discovered that folks at my school, the University of California, were thrilled to see expressions of solidarity coming from universities in Italy, Austria, and elsewhere.13Organizations like Edu-Factory are based at many universities in multiple countries.14There’s much more common awareness and perhaps convergence in strategies than even five years ago.

IB: I don’t know. I’m not very optimistic. It may be that we can push things in a good direction. But the opposing techniques of governance are very powerful, and they are pushing things in a bad direction.

CN: I was in Cairo earlier this month, and I read about these long periods in ancient Egyptian history between dynasties. Historians call them Intermediate Periods. They sometimes last hundreds of years. We are in an Intermediate Period.

IB: I don’t think this makes any difference for resistance. Governmentality is constituted by resistance to it—one of Foucault’s main insights.

CN: Agreed. I don’t like resistance. It tires me. It assumes a very long path between seeing the problem and actually doing something effective—think about flowchart illustrations and the long plodding from one cloud to another. It’s easy to sink into a cloud. Even worse is the lowering of expectations: resistance assumes the ongoing domination of the system one opposes, and it’s easy to never get around to constructing the alternative system.

IB: You want a revolution?

CN: Not in the sense of armed confrontation with the state, but yes, in the sense of delegitimizing what U.S. rule rests on now, which is a dead debate between right and center. I want an end to weak “liberal” resistance to a clearly unsuccessful capitalist-managerial paradigm that is neither efficient nor humane, that is not developmental in the sense of serving mass public needs in a world where the choice between mass suffering and mass creativity now involves billions of people. This deadlock between an outdated liberalism and a mentally paralyzed but emotionally entrenched, Maginot-line type American conservatism has now lasted my entire adult life.

IB: To be on the left is always difficult. Deleuze said that to join the left is to join a minority—there is no way around this. It’s not so different for the cognitariat, born into, and then having to work forever in, an environment it depends on but can’t really control.

CN: If we think of the cognitariat as the artist, it’s always been pretty bad. It got worse for the scientist too in the twentieth century—science now depends entirely on outside funding in large amounts, mostly coming from remote government agencies and corporations. The same thing has been happening to journalists, who watched their workplaces bought out by conglomerates with higher profit expectations while real journalism is largely migrating to the Internet. What about French social science?

IB: We have good research groups, and also a higher education sector that nearly everyone still sees as a public service.

CN: There’s a stronger sense in France than in English-speaking countries that public services are the foundation of good or at least nondestructive societies—that you don’t have civilization without them. But I find myself thinking about moving the practice of teaching outside universities. University overhead costs, especially for science, have become so high that the arts and humanities are getting pulled under in vain attempts to support the financing of high-end technology.

IB: There have been good models of this in France—Rancière’s alternative pedagogy, the Freinet method that developed “student-centered” teaching after World War I, which was very early, and linked up with the work of John Dewey among others. Do these inform your thinking?15

CN: I think about an academy standing next to the state school.

IB: That would be interesting, and I think too about finding something outside the CNRS. But I started out in the managerial world of enterprise, working in an advertising firm before I went back to school, and seeing what the competitive working world was really like. The only good thing about that was the company’s ability to support itself financially. But that’s what you don’t have very often with alternative schools. Now I benefit from my status as a public servant, and in the current context of indefinite precarity for intellectuals and artists I would think twice about abandoning that. I think this fear is also part of the current demobilization. If the counter-reforms are small enough, people will put up with them to keep their public sector status.

CN: France does have successful private schools.

IB: And with EU financing we have been able to mount critical projects—the EU helped support our critiques of benchmarking. But the ability to attract financing from a system that one denounces is limited. It’s a contradictory position, and these allow niches to flourish, but obviously not anything more than a niche. There are big psychological difficulties in finding oneself with a project and lots of ideas but without clear financial means.

CN: I agree, but staying inside creates major psychological blowback too. As I mentioned, I’ve been struck by the silence of the cognitariat. It has sunk quietly. The financialization of capitalism, the decline of the public sector and of the value of labor itself have splintered the cognitariat into a small group that works directly for political and business elites, and everybody else, who as you say are increasingly precarious and are also increasingly badly paid. The line runs between those who serve wealthy private institutions—patent attorneys who work for pharmaceutical companies, economists who work for major banks—and equally or better-educated people who work equally long hours in public service—history professors and firefighters alike—who have seen their status and pay stagnate for thirty years. I argued in one recent piece that we are seeing a return to the Three Estates that existed before the French Revolution—a tiny global elite, a Second Estate of its banker-lawyer-medical executive inner circle, and an enormous Third Estate that runs from doctors in general practice through nurses and teachers and on into blue-collar work and the informal sector.16 Conditions vary greatly, but the structural position of insecurity and decreasing social rights is shared by the vast majority of a population that includes most of the cognitariat. And it has been largely silent for three decades.

IB: This isn’t entirely true. There have been lots of researcher and teacher protests in France—almost every year, at various levels, and with real effects. Here we still see what things are supposed to look like. My ideal is to have public service funded by collective means. I grew up in a village where there was very little, but the schools were very good. They were well equipped academically. We had serious teachers, and lots of other activities—dancing, gardening, singing, traveling. I still have this image of the public school, based in a reality I experienced, in which there are sufficient means for teachers to institute their projects with plenty of autonomy. Teachers always take advantage of this kind of opportunity when available.

CN: So the cognitariat does speak, even within a regime in which they are ideal competitive subjects. It speaks through its work, and the everyday effort to make this work good. The cognitariat speaks through its instinct of workmanship, as Veblen called them, that it retains no matter what. For me, as an educator the craft involves the revelation of students’ individuality, helping students initiate actual intellectual projects of their own. I’m totally opposed to the waste of talent in a mass world, which is the real crisis of humanity—the inability to use more than a fraction of our abilities—and the crisis of the global population as the planet cooks in its own juices. Craft for me is connected to a world without leaders—it’s the creativity liberated by the decline of hierarchy.

IB: You’re an anarchist?

CN: OK.

IB: It does respond to the problem of competition: everyone forced into the same mold.

CN: Yes, and I just think of the colossal waste of ability, craft, invention, creation. I’d be happy to start some kind of service to help students with their projects. Only a fraction of the college-age population in rich countries like the U.S. and France experience an iterative educational process in which they discover their own strongest interests and have the intensive personal feedback that allows them to master the necessary techniques and do something great. Universities rarely teach craft. Elite private universities like Princeton require junior papers and senior theses conducted on a tutorial system, but that’s for the top 1% of any given national cohort. Why on earth do we think we can have a planet of six or seven billion people run by this 1%? It’s a problem even for the middle-class. The vast majority—say 90–95% of college students in the U.S.—are examined and ranked, but are mostly on their own in terms of personal development.

I have a friend in Lyon, linguistically brilliant, but whose parents could only imagine law school as the answer. She had no interest in the law and spent a couple of years being humiliated. Why wasn’t there a counseling service at her lycée that could have said, “Hmm, you love language and massively multiplayer online games. How about a combined program in the social sciences and social-network engineering, say, a program that develops theories of virtual communities?” Is that really too advanced for us?

The waste is the underdevelopment of craft ability in millions of college students every year—to say nothing of the rest of the planet’s population. This is the challenge of the twenty-first century—to not exclude the poor parts of the world, which the elitisms of our rank-based, competitive educational systems are currently designed to do, quite explicitly: keep them out!

IB: You want to create a consultancy for student projects? You want to privatize student advising?

CN: No, it wouldn’t privatize, the service would be complementary with the schools, and give poor kids the same kind of personal treatment that is now routine for the children of elites. Why not help them develop their own passions? It seems like a simple thing.

IB: What’s your idea of utopia?

CN: Actually it’s to be a novelist happily spending days by myself with my computer as an instrument of expression . . . I think what is missing is the realization of specific, situated experience, the making of interiority as rediscovered in the novel and then publicly forgotten by modernity, which rendered it as real as social facts, or as real as money. For me utopia is the craft process, and not the collective relations that bring it to bear, necessary though they are.

IB: We’ve both been talking about autonomy. When I talk about collective funding for education and research I’m talking about organizations that support it. Metrics and benchmarking are hostile to this autonomy within institutions.

CN: Yes, this is what the cognitariat really can speak about—the content of their work and the social structures that allow it to take place. You show that benchmarking blocks or fails to register the creation of self-organized groups that have always generated avant-gardes in art and innovation in other fields. The cognitariat speaks about its craft, and now has to speak much more about its social conditions. Art worlds and universities that don’t articulate and practice forms of social networks proper to their craft will get benchmarked into mediocrity.

×

© 2010 e-flux and the authorLabels: 4th world is now., christopher speak, cognitariat, competition, education, eflux, governmentality, isabelle bruno, political science, precarity, society